Every time I log on to Instagram, there’s a new ad trying to sell me a new dating app. One is described as ‘the Soho House of dating apps’, another as ‘Feeld without the bugs’. The latest that’s been flooding my feed is sponsored content for the app ‘Pure’. Their tagline reads, ‘Set your dating rules’. Their profile is full of pink Canva infographics about ‘How to sext like a pro’ and performance anxiety. It is sexuality sanitised and girlbossified, commodified and neatly packaged six slide posts about leather fetishes and something called ‘Breadcrumbing’. While the app positions itself as somehow radically different, culturally ‘queer’ and progressive, in its fundamentals it isn’t doing anything differently. Like so many other dating apps, it is wrapped up in the language of liberal sex positivity and neoliberal therapy speak.

All of these apps are vying to solve a problem they can’t quite define. They know there is something wrong with dating apps, something frustrating and draining, but they can’t place what it is. Unfortunately, the issue isn’t something fixable within the framework of dating apps. The problem is with the dating apps themselves. The inherent marketisation and self-commodification of dating apps creates a simultaneously stressful and mundane context from which we must attempt to build romance. First dates become like a job interview, trying to demonstrate to our Hinge match why we are the best candidate for the role of girlfriend (or more often, casual partner). In our profiles, our sites of digital self promotion, we must be simultaneously homogenised and differentiated. Homogenised enough to appeal to a broad base and the prevailing norms of contemporary dating culture, yet differentiated enough to catch someone’s eye.

To extend the metaphor of dating apps as a marketised experience, we seem to have collectively chosen a risk averse market strategy. Dating app profiles increasingly resemble each other. They can be easily divided into categories for consumption, a neatly packaged brand that can be fully comprehended in a five second glance over the three phrases and six pictures someone has chosen to encompass their whole self. Every man likes going for walks and Sunday roasts. Every woman likes Phoebe Bridgers or Arsenal Ladies. If, like me, you date arty guys in their late 20s/early 30s, he wants to get a coffee and go vinyl shopping. In an attempt at differentiation he’ll name drop an author or a musician or bar he likes, casually using these brand signifiers of identity to tell you what category of man he is. Is he a Cafe Oto guy or a The Blue Posts guy? Is he more Tolstoy or Murakami? Boards of Canada or Black Country, New Road? But these external signifiers of consumption as identity tell us little about each other.

I don’t claim to be any more enlightened on this front: my Hinge profile lists my “simple pleasures” as fresh baked bread, left wing literature, live music, dancing in the sunshine, and learning about something new. Most women in my broader social scene would describe themselves as such. What does this really signal about my identity besides my politics, which are shared by the vast majority of my demographic? Textual prompts serve little purpose beyond identifying that we are the same ‘type’ of person, from the same crowd, know the same cultural signifiers. Beyond this what more is there to someone’s profile besides deciding whether you think they’re hot?

So if they’re so bad, why do we keep using these apps? We all complain about them constantly, and yet here we still are. In a recent article for Dazed, Serena Smith draws upon sociologist Dr Rachel Katz’s work to examine how dating apps have become the only appropriate and socially sanctioned site for romantic connections. Serena observes that “These apps are increasingly regarded as the only space where flirting or romantic pursuit is acceptable, to a point where it’s even becoming common for people who feel a spark face-to-face to subsequently seek out each other on dating apps.” This seems like a substantial part of the problem, simply that there isn’t anywhere else to go. We seem to have sectioned off ‘the apps’ as the appropriate sphere for flirtation, making it increasingly taboo in other contexts. This makes sense as a risk averse strategy. Not getting liked back on Bumble is certainly less embarrassing than being rejected in person. Rejecting someone in person can be uncomfortable, especially if they are someone you see on a regular basis due to work or social circles. But to avoid risk is to avoid the very core of love itself.

In All About Love, bell hooks says that “Choosing to be fully honest, to reveal ourselves, is risky. The experience of true love gives us the courage to risk. As long as we are afraid to risk we cannot know love. Hence the truism: ‘Love is letting go of fear.’” This has never been more true than in the age of the apps. We pick out partners like a pair of shoes on ASOS, and similarly to a pair of shoes on ASOS, we throw them away as soon as they stop working for us. There are endless alternatives available at our fingertips, so why bother fixing this one? Another quote from hooks’ All About Love is relevant here:

“Then, treating people like objects is not only acceptable but is required behaviour. It’s the culture of exchange, the tyranny of marketplace values. Those values inform attitudes about love. Cynicism about love leads young adults to believe there is no love to be found and that relationships are needed only to the extent that they satisfy desires. How many times do we hear someone say “Well, if that person is not satisfying you then you should get rid of them”? Relationships are treated like dixie cups. They are the same. They are disposable. If it does not work, drop it, throw it away, get another. Committed bonds (including marriage) cannot last when this is the prevailing logic.”

To be certain, the market orientation of dating apps is not something unique to dating app culture. All About Love was published the year I was born, a long time before the prevalence of digital dating. The sociologist Erich Fromm describes a similar phenomenon in his 1956 book The Art of Loving, where he says, “In a culture in which the marketing orientation prevails, and in which material success is the outstanding value, there is little reason to be surprised that human love relations follow the same pattern of exchange which governs the commodity and the labour market.”

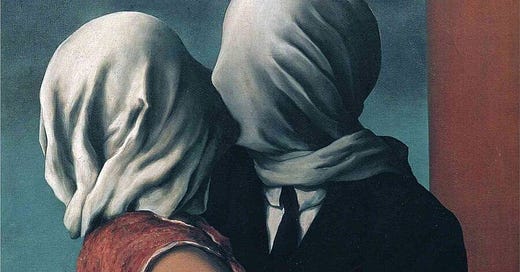

So are dating apps the problem, or a symptom of an increasingly capitalist and marketised worldview? There are certainly myriad problems with the apps themselves, especially with their addictive and discriminatory algorithms (a topic I’ll be exploring in my next essay), but most of the issues we find with dating apps are issues with digital capitalism more broadly. We are all entangled in the webs of personal branding, our digital avatars acting as masks through which we interact with one another, fighting for a glimpse of the real face hidden beneath. We will not, however, find a more selfless, sincere, and loving dating sphere merely by deleting Tinder. This ethos has permeated us all. A coffee shop meet cute is not exempt from the capitalist orientation. The market continues to prevail. Our concept of romantic relation is still dominated by economic models of thinking. We are performing cost-benefit analyses on potential partners, analysing our market competitors, trying to find the best option our social and sexual capital will afford us. This process is not quite emotionless, but it is dominated by the wrong emotions. Capitalist models of romance centre on jealousy, anxiety, and fear, rather than love, joy, and openness. It is individualistic and inwards looking, simultaneously obsessive about our wants and needs and hyper aware of the way others perceive us. We occupy the anxious dual role of salesman and consumer. As long as we continue to date within this capitalist marketised framework of romance, we will continue to be disappointed.

All that being said, I think there is hope. Much as the continuing climate and housing crises have led more and more young people to question capitalist hegemony, perhaps this crisis of love will lead us to do the same. Amidst the litany of complaints about dating apps, let me offer you a solution. Reject the apps, reject the market, reject the facade of indifference. Reject the risk aversion and the calculation. I encourage you all to let love blossom freely. Let it be platonic or erotic, romantic or otherwise. Approach it with empathy and sincerity. Take risks. Open yourself up to heartbreak, and in doing so you will open yourself up to love. It is only with a genuine vulnerability that we will be able to find genuine connection. This is not the whole solution, there is much systemic work to be done, but if we could all unplug from this framework, take some risks, and see each other a little more clearly, it would be a good first step.

This has been the first part of a two part series on dating apps. Subscribe below for a more detailed analysis of digital bias and nefarious algorithms in next month’s upload <3

The books I referenced in this essay are All About Love by bell hooks and The Art of Loving by Erich Fromm. You can buy all about love here, and you can find a free PDF of The Art of Loving here. You can also find Serena Smith’s excellent article, Did dating apps kills crushes?, here.

The thing that sucks for me is I always come back to them because it feels like an arms race. If everyone else is on them, and I’m not, and I don’t want to end up alone or end up settling, then it feels like I have to be on them. And it sucks. Thank you for writing this, I feel so vindicated

Great essay. I'm at a point where I think I need to delete all dating apps, I hate spending money and wasting time on them especially when I have so little success with them. It completely shatters my self esteem and any confidence I had that I can't look at them or bother trying anything with them for weeks.

It makes dating and meeting new people seem impossible especially as someone new to London.